Gillian Bryant and her family are stocked at 30 per cent, after losing 80 per cent of their herd in 2019.

PHOTOGRAPHY HANNAH HACON

Sign up to our mailing list for the best stories delivered to your inbox.

In February 2019, North West Queensland was flooded on a scale not seen in a generation. At the time, these women felt helpless, but within two years, their triumphs are evident.

WORDS JAYNE CUDDIHY PHOTOGRAPHY HANNAH HACON

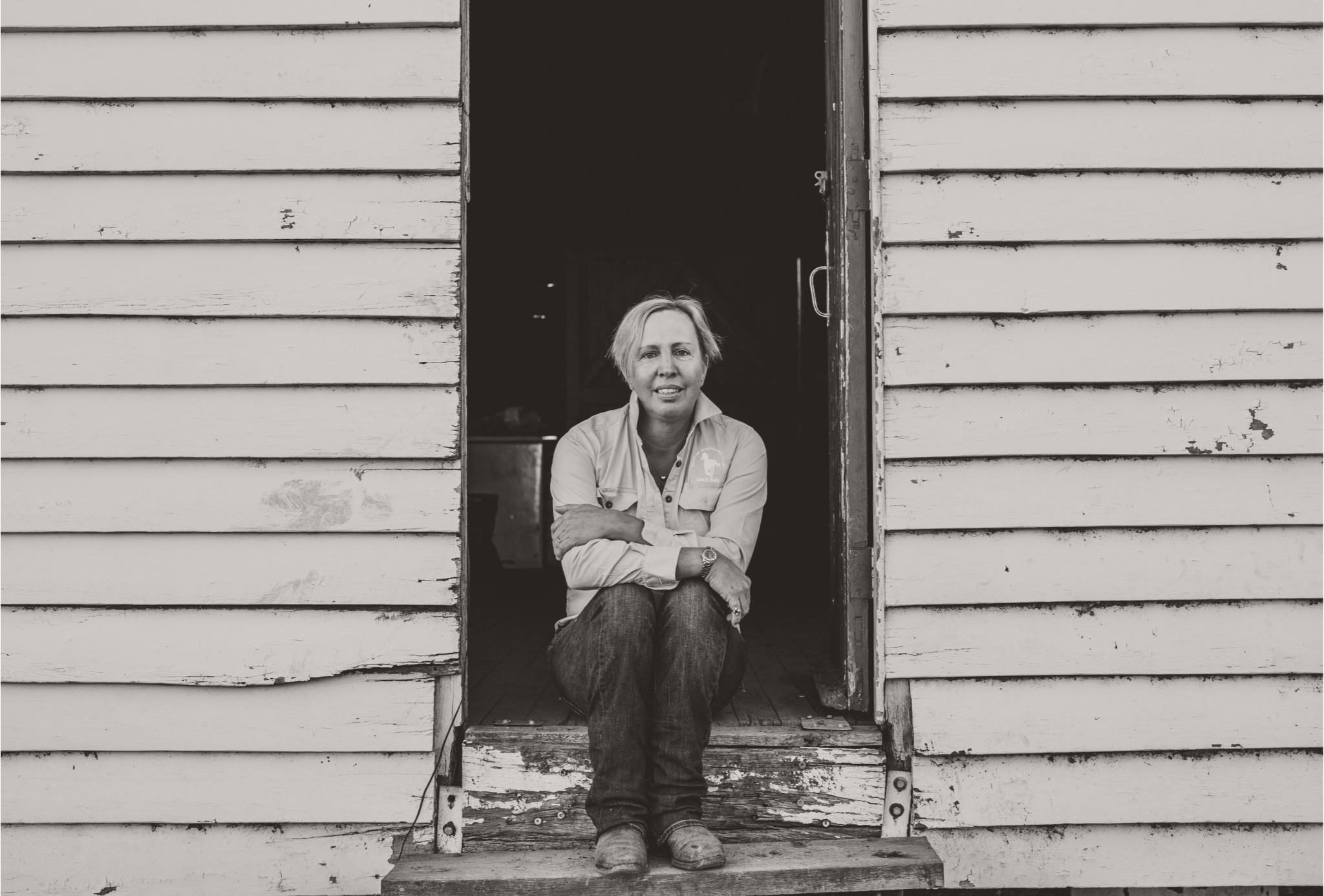

GILLIAN BRYANT

It’s been a long, slow road for Gillian Bryant and her family, who live on 12,140 hectares halfway between Julia Creek and Cloncurry. They are stocked at 30 per cent, after losing 80 per cent of their herd in 2019, and pasture recovery has been slow. “We haven’t been able to replace stock for a number of reasons, not least because there’s too much damage to the soil,” she says. “It’s been devastating, but we’ve always diversified and had other income. Grazing can be such a fickle industry and we’re always looking at the sky. You can prepare for drought, but you can’t prepare for what happened in 2019. It felt like the world had imploded.”

They had already sold two-thirds of their cattle before the monsoon because of a preceding seven-year drought and haven’t taken advantage of government recovery grants for replacement stock because their pastures wouldn’t be able to handle the pressure. “We essentially went from drought to flood, and then to drought again,” says Gillian. “We’re still really in the rebuilding stage. We’ve seen no response from the perennial grasses and the soil was so damaged we can’t put more pressure on it by replacing stock. We just need to wait and let the pastures recover.”

COURTNEY HAY

Courtney Hay was one of the famed ‘Angels of the Sky’, piloting a helicopter for Stanbroke on Donors Hills. She witnessed the loss of 6000 head over the 263,045 hectare property, 140 kilometres south of Normanton. “We didn’t get a chance to let it sink in,” she says. When the waters subsided, Courtney and her partner went to the Northern Territory for a reset, but have returned to Donors Hills married and awaiting their first baby’s arrival. These days, Courtney is happy to swap her joystick for a pair of fencing pliers and stay on solid ground.

JAYE HALL

Jaye Hall still struggles with the amount of trauma her livestock endured on her 18,210 acre property Caiwarra Station, 46 kilometres out of Julia Creek. She and her husband Ben lost half of their stud cattle. “The cattle were completely traumatised, and I’d never seen them so poor. They needed a gold star for surviving.”

The couple have been slowly rebuilding their herd, and are having renewed success marketing their

bulls; a triumph close to Jaye’s heart. “There’s no use dwelling on it. Country people are pretty resilient,

and we had so much help from friends.”

THEA HARRINGTON

Thea and Dudley Harrington manage Werrina Station, 36 kilometres from Julia Creek. She doesn’t count their losses in numbers. “A loss is a loss,” she says. Instead, she concentrates on how her family and community have come together through shared experience with a renewed focus on community, resilience and empowerment. “For me, the legacy of the floods is the creativity, innovation and ideas that have brought the community together,” she says.

The couple became parents for the first time last year, distracting their family from the stress in the paddocks and giving them a fresh new perspective.

“For me, the legacy of the floods is the creativity, innovation and ideas that have brought the community together.”

TANIA CURR

Tania Curr and her husband Phillip own properties around Julia Creek, but live on Arizona, 160 kilometres north of the township. They had a self-described kneejerk reaction to the flood, immediately offloading a property, thinking the 5000 head stock loss would cripple them. It didn’t. In fact, they not only bought more cattle in the months after the devastation, but have been building a more diversified property portfolio.

“We can’t change what’s happened, we have to move forward, and we’ve shifted focus,” she says. “Neither of us are averse to risk or taking on challenges, so we’ve now purchased a block at Barcaldine and another in central New South Wales to spread the risk.”

AMANDA MCMILLAN

Amanda McMillan’s family had a period of rebuilding, recovery and rebirth in 2019, purchasing two more properties in the aftermath. She now lives at Wollogorang Station in the Northern Territory, an hour away from Doomadgee.

“We always joke it was our own ‘Steven Bradbury’ moment,” says Amanda. At the time, purchasing more property felt impossible. “In those early days, many women had to become many things, and at a much faster rate than the rains took to take our livelihoods.

“We have moved on and are focussed on our business development and the raising of our two beautiful boys in a climate that encourages ‘free range’.”

EDWINA HICK

For Edwina and Patrick Hick at Argyle Station, north of Julia Creek, prospects are looking brighter. The couple aim to run 15,000 head of cattle across five properties and estimate to have lost 6000 head over 200,000 hectares during the 2019 event.

Despite the personal losses, Edwina has been a driving force behind some of the community organisations that have brought people together socially and emotionally.

“We recognised the importance of just having an outlet and something to draw your focus away from what was happening at home, because people really didn’t know where to start,” she says.

“We have a pretty amazing little community. When the chips are down, they do pull together.”

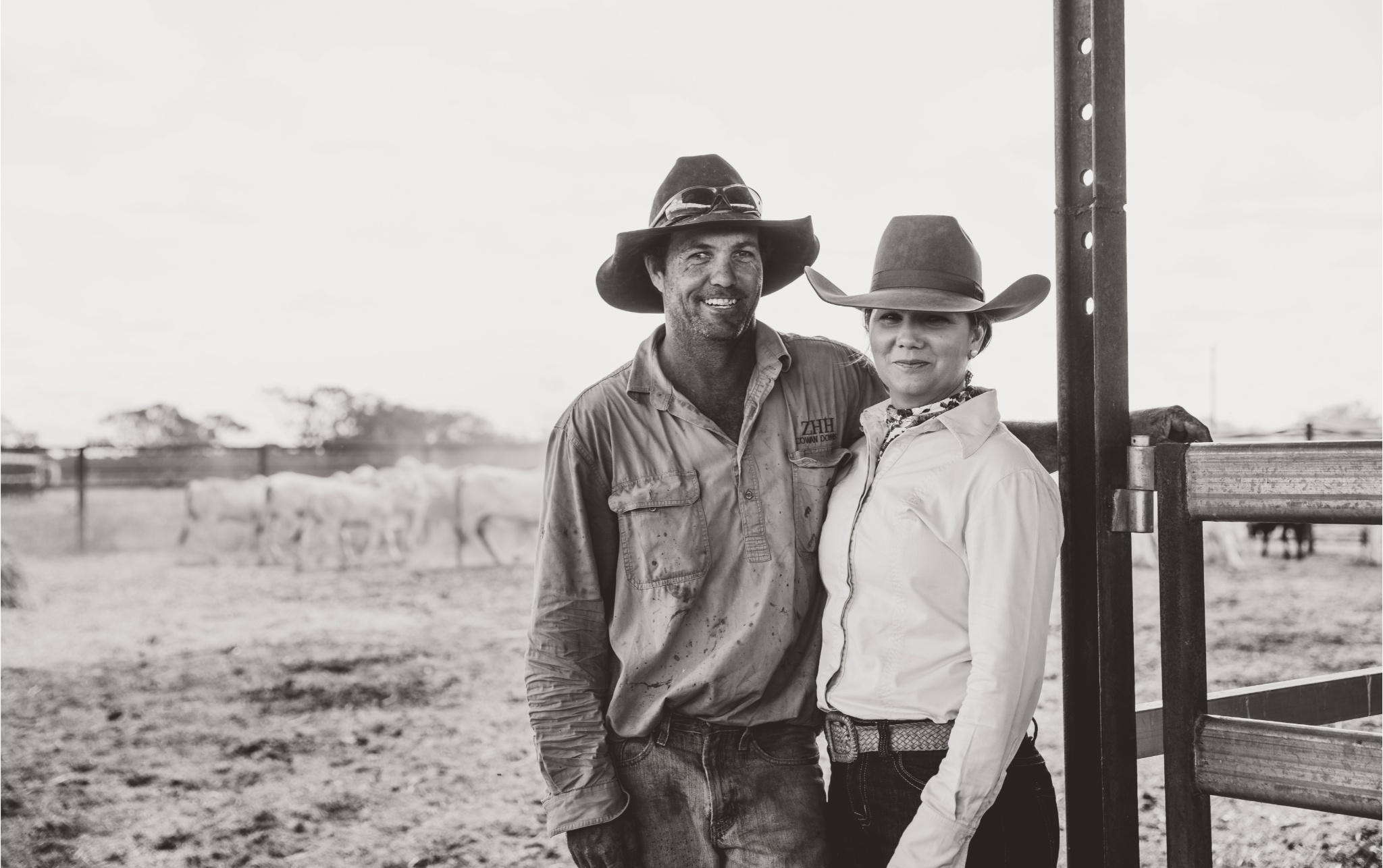

CHERI STANGER

Life is good for Ben and Cheri Stanger. They were in the epicentre of the 2019 rain event while managing Cowan Downs station, situated about halfway between Cloncurry and the Gulf of Carpentaria. They witnessed 4500 head of cattle that they’d nurtured perish and decided to change tack and purchase the iconic Burke and Wills Roadhouse, 40 kilometres up the road.

“We’d always driven past and seen a lot of potential and thought we’d have a crack,” says Cheri. “Our first year of business coincided with the COVID outbreak but we were still booked out for accommodation.”

Subscribe to Graziher and never miss an issue of your favourite magazine! Already a subscriber? You can gift a subscription to someone special in your life.

To hear more extraordinary stories about women living in rural and regional Australia, listen to our podcast Life on the Land on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and all major podcast platforms.

The Kalkadoon women capture the colours of Queensland’s Gulf Country as co-owners of Cungelella Art.

Rozzie O’Reilly’s earliest memories are of helping her mum on the farm.

After moving to Yass in 2011, Jodi thought it would be simple to pick up a pure merino wool jumper to keep out the chill.

As a student of Haileybury Pangea’s “online campus”, Marly Wright can pursue her passion without sacrificing her schooling.

Some vendors drove 12 hours to be at Sarah Knight and William Clarke’s big day.